“Before joining Ravok, I worked in the finance departments of two major legacy studios. I’ve prepared waterfalls, attended the monthly meetings where greenlights happen, and I’ve signed off on the quarterly reports.

But the most interesting documents I ever handled weren’t the public filings. They were the internal participation statements—documents sent to writers, directors, and actors explaining why, despite their movie breaking box office records, there was absolutely no money left to pay them their ‘net profit’ share.” — Thibault Dominici, CFO, RAVOK Studios

What Thibault is describing has a name: Hollywood Accounting — A standard industry practice designed with one goal: ensure a film never technically shows a profit on the books, and avoid payouts to backend participants.

Let’s dive deeper.

The Case Study: The Magical Loss

Back in 2007, Warner Bros. released Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix. A massive global success.

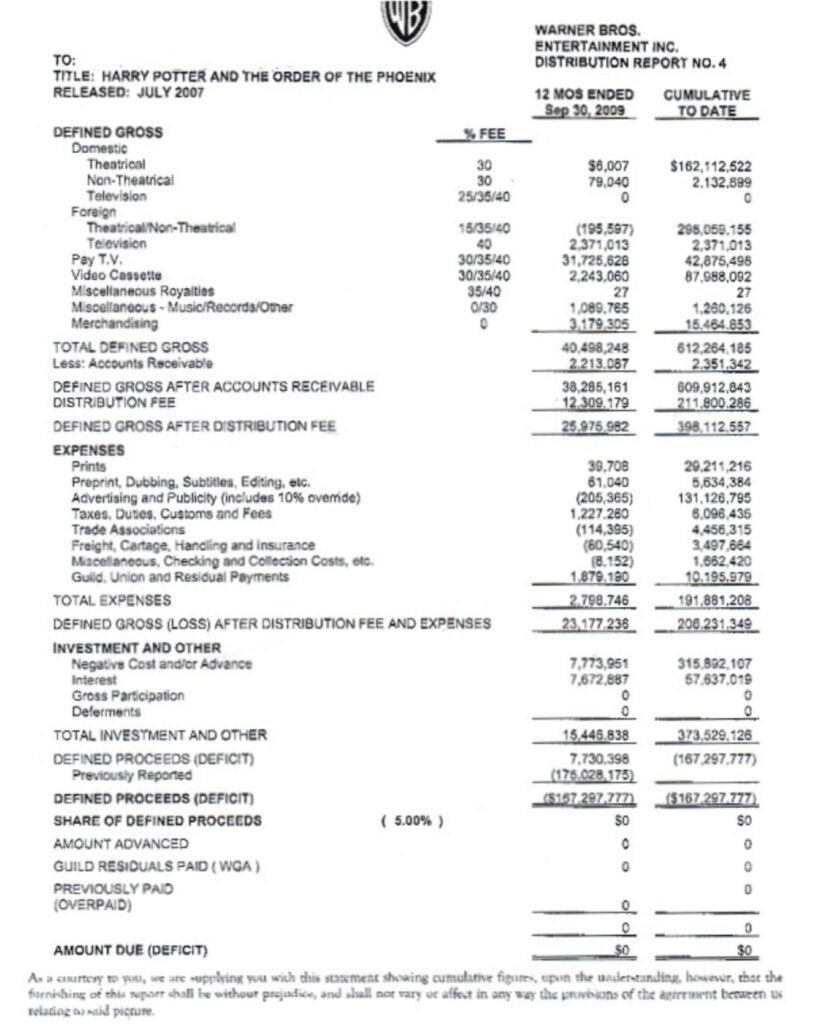

A few years later, a net profit participation statement for the film was leaked to the press. It showed that, In the first 2 years, the film generated over $600 million in worldwide gross receipts (box office share plus home video/TV licensing revenue that flowed back to the studio).

Yet, according to the studio’s accounting…the movie had actually lost $167 million.

So how do you turn $600 million in revenue into a $167 million loss? A tip; it’s not magic. It’s accounting. a deliberate system of fees, overheads, and interest charges designed to drain the pool dry.

Here is a simplified breakdown of how that “loss” was manufactured, based on widely circulated analyses of that leaked statement.

Step 1: The Top Line (The Money In)

- Total Gross Receipts (“Defined Gross”): $ 609,912,843

This should be enough to cover the Production budget of $150 million and distribution expenses, right? Let’s have a look.

Step 2: The “Gross” Participants

Before the studio starts its accounting tricks, the biggest players get paid. Think stars and creators with enough leverage to demand “First Dollar Gross” and residuals.

- Less: Guild, Union and Residual Payments: ($10,195,979)

- Remaining Balance: $ 599,716,864

Step 3: The Studio Pays Itself (Distribution Fees)

This is where Hollywood accounting gets controversial. The studio charges the film a “Distribution Fee.”

In essence, Warner Bros. (the production entity) pays Warner Bros. (the distribution arm) a percentage of the revenue to handle the distribution. These fees are percentages set by the distributors, usually between 25% and 40% of various revenue streams.

It is profit shifting from one pocket of the conglomerate to another, but it is treated as a hard “cost” to the film, because if Warner Bros. was just a Producer and not a Distributor, they would need to retain a third-party distributor who would charge similar percentages, or maybe a bit lower.

- Less: Distribution Fees (approx. 35% avg): ($211,800,286)

- Remaining Balance: $ 387,916,578

Step 4: The Actual Costs (Mostly)

Now we deduct the tangible costs of making and selling the movie.

- Less: Advertising and Prints (P&A): ($131,126,795)

Marketing a global blockbuster is incredibly expensive, but those costs could be capped.

- Less: Other Distribution Costs: ($50,558,435)

We could argue that this is too much, but this should be verifiable costs related to the exploitation of the film.

- Remaining Balance: $206,231,348

Step 5: The Insult to Injury (Production costs + Overhead and Interest)

This is where it gets really bad, we now have to deduct the “Negative Cost”. This is all the money spent by the producers to make the film a reality.

- Less: Negative Cost: ($315,892,107)

It makes sense to reimburse whoever paid for the initial expenses to make the film. The actual Production budget is kept confidential, but the consensus is that it was around $150 million. The deduction is however $315 million. The additional $165 million of costs is not explained.

Studio Overhead: The studio typically charges an automatic 10-15% fee on top of the production budget to cover corporate office space, executive salaries, and the electric bill. They charge the film for the privilege of filming on their lot, even if they own the IP.

If we are being generous, we can assume that the overhead is not included in the $150 million production costs, but only explains ~$20 million of the additional $315 million.

Any costs in addition to the production budget would typically be for some initial marketing to get the film distributed, but in that case distribution was a done deal before they started filming, so this massive deduction is the biggest hit to the profit of the film.

It is also interesting to note that the Negative Cost grew another $7.8 million in 2009, which means the production arm keeps spending/charging large amounts 2-3 years after production ended.

- Less: Interests: ($57,637,019)

Interest: The studio finances the film. They then charge the production “interest” on that money until the film pays it back. Because the studio controls when revenue is recognized, they can ensure the film carries that debt—and keeps accruing interest—for years.

It’s like having a credit card where the bank sets the interest rate and also decides when your payment gets processed. It’s fair to pay the financiers interests, but the studio had to front the $150 million production costs, and already recouped $213 million in distribution fees alone, yet, interests keep accruing on the “unpaid” amount.

If you were a writer or a mid-level producer on this film, and your contract said you were entitled to “5% of Net Profits,” your share amounted to exactly $0.00. Same to producers.

The studio made over $400 million in distribution fees and overhead, and keeps charging interests. The top stars made millions in initial fees + residuals. The “net” participants got nothing. Backend turned into a ghost story.

But what if the math was clean?

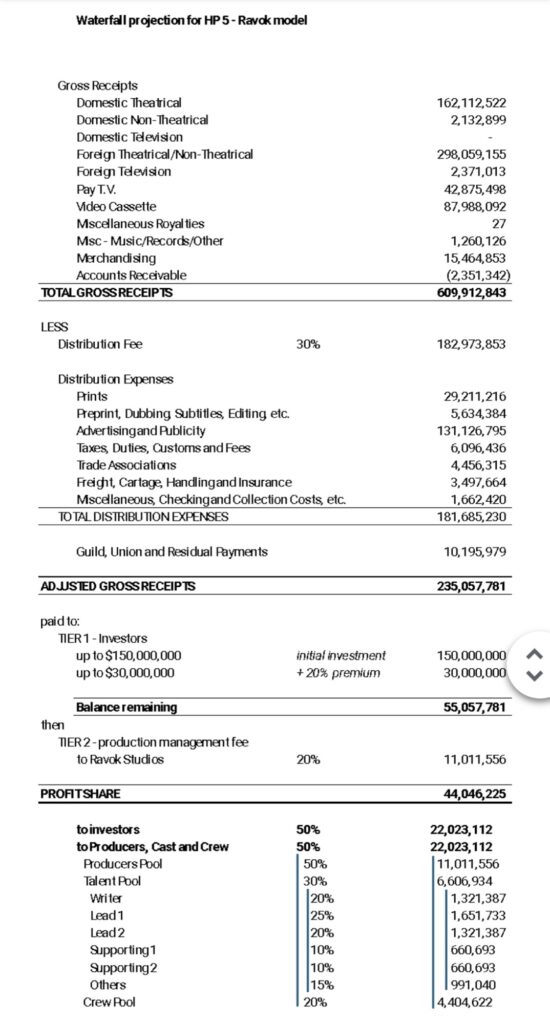

Let’s take that same $610 million Harry Potter leaked statement and run it through RAVOK’s model.

Disclaimer: We are assuming the same Residual Payments and Distribution Expenses, even if it could be lowered.

The Calculation:

- Total Gross Receipts: $610 million

We immediately deduct the actual costs. No internal fees.

- Less: Actual Distribution Costs: ($182 million)

- Less: Third party Distribution Fees (capped at 30%): ($150 million)

- Less: Actual Production Budget: ($180 million)

- Less: Residuals: ($10 million)

- Financing Fees paid to investors on top of production budget (Flat 20%): ($30 million)

= THE PROFIT POOL: $55 million

This is the real pot of money the film generated after paying its actual debts.

Under the old model, this number was negative $167 million. Under RAVOK’s model, there is a surplus of over $55 million.

This is the pool from which our partners (writers, directors, key creatives) would draw their share, same as us and other producers.

If that same writer mentioned earlier had a share of Ravok’s model instead of 5% of standard Net Profit, their check wouldn’t be zero.

The difference between $0 and $1.3 million isn’t better marketing or a higher box office. It’s simply changing the accounting definition from one designed to hide money to one designed to share it.

At RAVOK, we view the traditional model as archaic. It incentivizes distrust for talent and investors alike. If creative partners feel cheated by the accounting department, they won’t bring their best next idea to us. If Investors feel cheated, they won’t deploy capital into film. The system will keep repeating itself.

The legacy studios cling to the old ways because it protects their downside and maximizes their control. And yet, even with all that extraction, they still drown in debt and resort to desperate mergers and risk – averse stories. The infrastructure that once let them justify to force talent into bad deals is becoming outdated. With the evolution of technology and the growing fintech market, the access to build a transparent, equitable model is clearer than ever. Change needs to happen, otherwise, how can film ever evolve to be considered an investable asset and successfully raise capital in the indie world? – Amanda Aoki, Ravok’s Founder

In the next article we will dig deeper into RAVOK’s model and differentiations. But In conclusion for the meantime “Hollywood Accounting” is nothing but a relic of an era where information was scarce and studios held all the cards. That era is over. The landscape is shifting. Distribution is democratizing. Talent is getting smarter. The industry is starving for a change.

By : Amanda Aoki and Thibault Dominici

Related Reading

- Hollywood’s Original Sin: How Broken Development Destroys Everything

- Why Hollywood Needs a Startup Revolution

Ready to build with us? Partner with RAVOK | Learn About Our Model